High streets in towns across the country have been, for over a decade, dying a painful death. It’s a familiar sight. Boarded up shops and an emptiness showing local economies and cultural hubs that once were. This has been particularly noticeable since the 2008 financial crash, compounded even further by a decade of damaging austerity, sucking out money and weakening aggregate demand in the economy. In the decade following the financial crash, Borders closed, GAME shut half its stores, Comet closed and JJB Sports disappeared. British Home Stores went into administration, along with Woolworths, Maplin, Toys R Us and Debenhams. Coronavirus has accelerated the high street’s demise with Edinburgh Woolen Mill going into administration, along with Harveys Furniture, the UK’s second-largest furniture retailer, TM Lewin, Monsoon and many others. The rise of working from home has not been enough to arrest this trend. In early September, a study estimated 125,000 UK retail jobs were lost already this year. Experts warn of up to 300,000 retail jobs being axed as a result of Coronavirus significantly accelerating trends that were already underway. A place’s sense of self worth declines when all around are closed shops and the most likely prospect of sustainable work is a delivery depot, where workers endure precarious work, bad conditions and low pay.

The numbers of retail job losses this year are staggering when added on to those from the past couple years. 2018 saw 150,000 jobs lost, with another 143,000 lost in 2019. What replaces these shops is a familiar and depressing sight for many towns across the UK: a betting shop, fast food outlets, and pound shops. These are all the result of political decisions and choices, not the inevitable consequences of an immutable higher force.

This results in a profound sense of loss, with high streets formerly providing a bustling hub of exchange beyond purely economic, but also social and cultural. Especially in smaller towns which are more rural and isolating, the high street’s demise is a devastating experience – jobs are lost to never be replaced, places where friends once met disappear, optimism fades. A grinding abject sense replaces it.

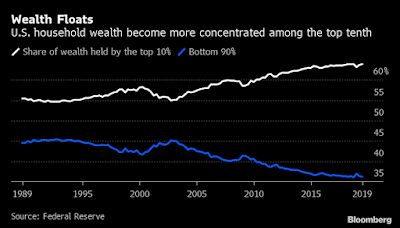

The Tories needless and devastating austerity has pushed millions into poverty, extracting money out of the economy, with significant reductions to Universal Credit. It has also starved councils of central government funding, where core funding to London councils has been reduced by 63% in real terms, with northern cities affected the worst, where seven out of 10 cities with the largest cuts are in the North East, North West or Yorkshire. The results have been devastating, regional inequality in the UK is the worst in northern Europe, and one of the worst in the developed world. The UK has 9 out of the 10 poorest regions in northern Europe. As well as devastating citizens and communities, food bank Britain sees ‘systematic’ and ‘tragic’ poverty according to the UN’s special rapporteur, the effect this has had on the high street is also profoundly devastating. Beyond individuals having less to spend, ideological cuts have made councils more reliant on business rates. This provides council with a problem: they are incentivized to have higher business rates due to inadequate funding, but the result is if they ramp up rates, more empty shop fronts will likely appear. While small and medium businesses potentially become subject to higher business rates, the exact opposite is happening to the behemoth that is largely responsible for the high street’s demise.

Amazon – aggressively avoiding tax

The chief beneficiary of the high street’s decline is Amazon. Its exorbitant wealth has ballooned since the pandemic, with revenues in the third quarter of this year showing a 37% increase in earnings, with company revenues at $96.15bn, compared with the net income of $2.1bn in last year’s third quarter. These figures are astronomical and run directly anathema to the amount of tax it pays: just £220m in taxes in the UK last year, despite sales revenues here of £10.9bn. This year, it is paying just 3% more tax last year despite its profits rising by more than a third. A study in 2019 by Fair Tax Mark puts Amazon, run by the world’s richest person, Jeff Bezos, as the worst offender for ‘aggressively avoiding’ tax over the past decade. It outlined how Amazon’s effective tax rate over the decade was 12.5%, when its headline tax rate in the US had been 35% for most of the decade.

The UK’s new digital service tax will not affect Amazon, yet small traders who sell products on its site will face increased charges. This would be easier to stomach if Amazon did not make 74% of its workers avoid using the toilet, sometimes urinating in bottles, out of fear of missing target numbers. This follows, as Kalecki wrote, capitalists want discipline in factories, which the threat of the sack achieves. Amazon also uses new software to track trade unions, undermining one of the most fundamental rights any worker has. It is unsurprising, then, that 55% of Amazon employees have suffered depression since working there, and over 80% said they would not apply for a job at Amazon again. This continues the privatization of stress that Mark Fisher powerfully wrote against, where those subject to deteriorating conditions, which are deemed ‘natural’, look inward to their brain chemistry, or personal history for sources of stress. So it is that workers are subject to the disciplining and dehumanizing effects of neoliberalism, mirroring what is seen for those out of work and subject to the brutal punishment that is Universal Credit.

Beyond the toxicity and harm Amazon inflicts upon its workers, its effects on the high street are similarly troubling. It has taken 25 years for Amazon to assume its monopolistic position where its size, predatory trading, ability to dodge tax and use of data work to put retailers out of business. In another 25 years, if current trends are not reversed, individuals will not be able to shop at many, if any, other retailers. This comes as Amazon plans on launching at least 30 physical stores across the UK, where an app is used to enter the store, with customers not required to pay for purchases at checkout tills, giving a different meaning to fast-food culture. If it sounds like a data grabbing dystopia, that is because it is.

Platform and Surveillance capitalism

Amazon, unlike local retailers, operates in a different economic stratosphere with a wholly different economic model not open to smaller firms: platform capitalism. As Nick Srnicek persuasively argues, platform capitalism has grown, with the rise of companies like Google, Amazon, Facebook, Microsoft and Uber. These companies provide the hardware and software for other actors to operate on. These big tech giants are platforms that are predicated upon a voracious appetite for data, disregarding privacy and workers’ rights, as they constantly expand. Connecting all these tech behemoths is the centrality of data, which is the basic resource driving them, and providing them with an advantage over competitors. Platforms are designed to extract and use that data. They have the benefit of providing infrastructure and intermediation between different groups, monitoring and extracting all interactions, providing their economic and political power.

These platforms, Amazon included, have a trend towards monopolization. A vital feature is their reliance on network effects, where the more users using a platform, the more valuable the platform becomes for everyone. Just as individuals become interested in buying from Amazon when there are enough products available, once users arrive, retailers double down and populate the platform further still. Both sides feed one another, with Amazon taking a margin on every item sold. Further, Amazon created greater network effects with ratings and reviews, along with a feature showing other products that customers tend to buy. Conversely, shoes bought at a local store cannot tap into such network effects, yet the shoe store is subject to higher tax rates too.

As Shoshana Zuboff writes, platforms’ eternal need for more data means they are driven to push up against the limits of the private realm. When this drive is combined with more computer monitoring and automation; the desire to personalize and customize services offered to users of digital platforms; and the continual experiments on its users and consumers, we end up with what Zuboff terms ‘surveillance capitalism’. The possibilities of using personal data to target consumers more accurately is a trend that cannot be resisted across the big tech monopolies. The justification against is that doing so would result in a loss of a competitive advantage. Technological advances have contributed to flagrant invasions of privacy, as demonstrated by Amazon’s Alexa, a voice assistant that always listens to conversations, where Amazon “is able to anticipate and monetize all the moments of all people during all the days”. We, ultimately, are the sources of surveillance capitalism’s surplus.

Surveillance capitalism operates as a cause for, and consequence of, the high street’s death, the predatory vampire like way it feasts not only on the blood of retailers, but it also “feeds on every aspect of every human’s experience”. Individuals become subjugated to imperatives that are not theirs with autonomy undermined.

Friedrich Hayek, leading intellectual architect of neoliberalism, argued in The Road to Serfdom, that abandoning freedom leads to a loss of freedom and the creation of an oppressive society, and the serfdom of the individual. It was, so the theory goes, up to the market to liberate us all. And yet, it is instead the deregulated free market that has resulted in the oppressive conditions of Amazon warehouses, which are anything but liberated, with workers urinating in bottles out of fear of the sack. Compounding this, our everyday lives being scraped and sold to fund Amazon’s monetization off our everyday behaviour and subjugation is only liberty for Jeff Bezos, but our collective serfdom.

As Alan Bradshaw writes, the normalization of subscription services like Amazon, extracting consumer spend via direct debits rather than point-of-persuasion, helps move ever closer to a world of automated shopping. Big data’s use of algorithms edges society towards social control, where the advantages for business are prioritized without any considerations for exploitation. The illusion of technological inevitability coupled with the natural collapse of the high street is appealing yet misleading. There is power in revivifying the public sphere.

Community wealth building

An effective tax regime is the first step to changing this trend, helping to raise substantial revenue from Amazon and other tech giants. Once the virus is contained, reconstruction offers an opportunity to depart from the neoliberal orthodoxy that is killing the high street and what is needed is a revivified public sphere, exemplified by community wealth building, or ‘the Preston Model’. The model works to embed capital in the local community and relies on combining the economic weight of ‘anchor institutions’, like schools, hospitals, universities etc. These institutions procure contracts with local businesses, which attach certain conditions, for instance, a catering contract in a hospital open only to worker-owned enterprises based within 10 miles. This ensures capital, rather than being extracted by large corporations and leaked outside of a local economy, stays within a local economy, boosting local employment and future investment. These contracts are only entered with unionized businesses, cooperatives and companies that operate in the local area and paying a living wage, ensuring there is no race to the bottom, avoiding the horrors apparent in Amazon’s warehouses.

The results of this model are profound. Research from the National Organisation for Local Economies found that anchor institutions spending in the Preston economy increased from £38m to £11m in just three years, improving all economic measures, including GDP and productivity. This has led to Preston recently being named Britain’s most improved city in the UK, as well as the best place to live and work in the Northwest.

This model enables worker-owned businesses to grow but without access to credit the possibility of expansion is limited. That is why a network of regional investment banks is essential to the success of community wealth building. Regional investment banks would be crucial to the growth of this sector, which is presently inhibited by commercial banks’ tendency to steer clear of such investments. Local authority pension funds could also be encouraged to redirect investment from global markets to local schemes for further means of financial support.

Reviving the high street, beyond the Preston Model, must include reforms to public transport. A high street cannot flourish without being easily accessible. Due to austerity cutting local bus routes by 32% and the rise of ticket prices, huge swathes of the UK are unable to access public transport. It is essential that public travel links are reinstated, and expanded, extending initiatives like the freedom pass, which enables over 60s to travel for free. Renationalizing the railways and ditching the approach that prioritizes shareholder profits above all else would also assist with lowering fares.

Finally, establishing rent caps to reign in unscrupulous landlords, appropriating derelict or unused properties into community trusts, and reforming business rates must be a part of a broader project to revive the high street. These are all commonsensical, and also democratic, allowing local communities to decide what will replace certain retail outlets when they do disappear. This could be a cafe, a hairdresser, a care or centre for learning. Society’s needs, not those of the market, must shape change. Germany's economy is often heralded as one that is dynamic, innovative and impressive, yet its use of both regional investment banks and rent caps is all too often forgotten or conveniently ignored.

The Preston Model, coupled with these reforms, would not stop platform and surveillance capitalism, but would at least attempt to break away from the deleterious trend of Amazon, a data grabbing tech giant invading privacy, undermining worker rights and killing local high streets. It aims to drive standards up, for those of local economies and its workers. It could also trigger a greater push for localism across other economies too. And it is popular, with 55% preferring to buy local brands to help support local and small producers.

Regaining control

The high street's precipitous decline is being caused by an economic model working to benefit surveillance capitalist platforms like Amazon. Its effects are devastating, haunting high streets, instilling a sense of loss and despair, and potentially replacing some jobs with precarious work. It also works to undermine our liberties, well-being, privacy and autonomy by, harvesting every detail about us possible through our personal data, with the aim of making profits. The commodification of this personal data serves to enrich Amazon's stranglehold of different markets and our collective selves. The coronavirus crisis has accelerated the trend of a declining high street, leading to even more local shops closing across high streets nationwide, due to social distancing and lockdowns mandating the closure of non-essential shops. However, this pause offers a chance to push for changes to an economic model that is failing. Whilst it is impossible to wholly insulate local markets from globalization, communities must take control. It is time to encourage local development, where jobs are sustainable and made locally, rather than lost. Better working conditions, stronger local economies and a healthier collective space for communities are all commonsensical demands.

It seems implausible that the Conservatives would truly grasp the problem - as they have done nothing over a decade in office but assist this trend and they cannot even get Amazon to become subject to a digital services tax - yet alone propose the solutions required to allow people to actually take back control. It is therefore vital that Labour make the case as forcefully as possible. If they do not, they will allow the Tories to set the terms of debate around regional inequality and localism, which will shift from economics to cultural issues, likely blaming immigrants, immigration whilst failing to address the economic causes of the problem. The lack of opportunity and abject sense of bleakness against London and finance capital was a key component of the vote for Brexit, and it is pivotal the left focus on trying to solve that, rather than placating a sentiment hostile to immigration. The longer Starmer’s Labour stays silent on policies such as reviving the high street, the easier it will be for the Tories to ramp up the culture war to distract from their litany of failings. To not act, or to delegate it to the ‘invisible hand’ of the market is to choose a high street of gambling shops, pawnbrokers, and precarious work degrading the environment. We all deserve so much more than that.