The club experience is a collective one. Its power comes from people feeling the same thing in the same space at the same time. That feeling of losing oneself in a dark room, with a low ceiling, being disinhibited and carefree is unlike anything else. The strength of emotion and passion felt when dancing like nothing else matters, because, at that exact moment, nothing else does. It is a powerful, exhilarating and otherworldly escape. It’s a chance to forget about the how the country is becoming a progressively more hostile and inward looking place. It’s an opportunity to forget about how the young will be on average be poorer than their parents, with greater debts, entering a worse labour market with more precarity and needing to rapidly decarbonise the planet after neglect by previous generations. It’s an invitation to temporarily ignore the fact that the future, especially for young people, is looking increasingly bleak, along with the rise of bullshit jobs, where a growing amount of people feel incomplete in the knowledge their job adds no value and thereby makes them feel unfulfilled. Neoliberal Britain before the pandemic could feel like a grim monochromatic place - with dreams dashed, hopes eroded, creativity stultified. And now, with economies locked down, clubs closed and physical distancing in place, the cathartic release that came from losing a part of yourself, and your independence, and being glad to “when your brain pulses with the same validation of being with so many people who have chosen the same path” is something that is being sorely missed by many club-goers.

Following a week at work in a job that often feels like your creative potential is sapped by increased bureaucratization, the nightclub offers an escape. After turning up to work, obeying your boss and competing with your neighbours, the nightclub offers a an intoxicating way out and a disruption from the monotony and banalities of late capitalism. There is a cruel irony at play that an ideology so focused on individualism, turns and churns individuals into zombie consumers who are robbed of their creativity, individuality and uniqueness. And yet, the nightclub provides an opportunity to immerse oneself in a positive, permissive atmosphere of unity, joy and euphoria.

There has, however, been an increasing commercialization that has affected clubbing. Nightclubs, like the legendary Plastic People and London Astoria, have been closing for over a decade, due to a toughening up on licensing laws, a clamping down on so-called ‘public nuisance’ and the increasing prevalence of capital and private real estate sucking the character out of cultural hubs. Rents have been precipitously increasing due to the flogging off of social housing and the greed of profit seeking vultures like buy-to-let landlords and property developers, as well as successive governments failing to adequately build social housing for over 40 years. Rather than changing the character of an area through social cleansing or gentrification, this gets branded as ‘regeneration’. The results are usually devastating, with London boroughs looking increasingly the same: a Pret here, a Tesco Express there, a closed pub or club, and a newly built block of privately developed flats that are anything but affordable. This pushes out those who used to be able to afford to live in the area. Culture becomes replaced by capital. This is part of the reason why clubs remain a cherished hub, offering a chance to form a break, however temporary, with the notion that social relations are dictated purely for and by financial reasons.

Clubs that survive are not immune from increasingly competitive financial pressures, resulting in a commercialization inside the club. With entry prices rising to meet escalating rents, those seeking solace in a nightclub have to fork out more than ever. With overpriced drinks too, it can sometimes feel as if fun and communal subcultural spaces are themselves being commodified. As anyone who has been to Printworks in Surrey Quays, a nightclub in the former Harmsworth Quays printing plant can attest. Beyond the protracted queuing, and the at £30 ticket (at the very least), there is an additional further £10 to be forked out for having the privilege of a locker, with the communal cloakroom being eschewed for this venue. The token system also works to capitalize on intoxicated people forgetting to get refunds. It is easy for such a night to end up being in excess of £50 per person. The venue itself boasts a capacity of up to 3000 people, and it is undeniable that the atmosphere is less enjoyable as a result, often more rowdy and lacking the intimacy that comes from being in a small club. The crowd feels energized, perhaps, but not in warm and receptive or empathetic way that smaller venues tend to. Compounding this, in my experience at least, has been the indifference to dancing or interacting with the music from many touristic attendees. It is a venue that is as easy to lose friends in, as it is to lose one’s mind, given the sheer vastness and confusing layout. And yet, its lights show is like no other, with an audiovisual pairing that few other venues in London can match. The lights are architectural, shape shifting between sets, coupled with a large 14 metre surface that has various visual content and an array of transfixing images, where it is hard not to be mesmerized by the visuals on show.

We often strive to give our lives purpose. Through engaging in specific activities we can provide a sense of autonomy. As Avi Shankar notes, the club provides such an opportunity, providing an apparent contradiction between overt sexuality and child-like innocence. Another contradiction comes from those who want to stay in control, whilst at the same time wanting to disengage from reality. It is this creation of a space allowing people to behave as freely as they want whilst also showing respect and warmth to others, which allows for the feeling of being in a community, instilling a sense of belonging to something greater than oneself. In the neoliberal age of increasing atomization, where a sense of community has almost been lost, this quest to freely become a part of something greater than oneself is why nightclubs are powerful experiences that provide more than an escape. It is that feeling of being together in public having a shared hedonistic experience that feels so enjoyable.

The spontaneity and uncertainty of not knowing where an evening of dancing might lead was part of the thrill. The surprise could involve a DJ seamlessly mixing records you have never heard, twisting, turning, and stringing a crowd along in the palm of their hand - in different directions, with scintillating, tantalizing and enticing undulations. Or, it could be the impulsiveness of ending up at an after party with a group of people you met earlier in the smoking area. Or, it might even be both. The possibilities seemed endless.

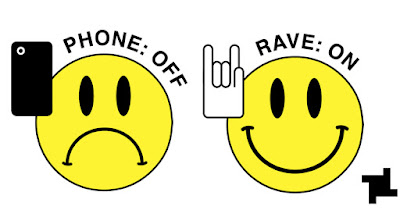

The intimacy of the nightclub is mirrored by its intensity. The sensation of a powerful sound system pumping a heavy bass through your chest, all the way down your body, through to your feet can make it feel like an out of body experience. The simplicity of repetitive rhythms works to induce a feeling of blissed trance. A feeling of oneness emerges with both the music and with those around you. And the music creates textures around you, caressing and surrounding you, as it comes at you from all angles, fully immersing you in the experience. It is something that cannot be captured by any smartphone. With the increasing trend of London nightclubs banning phones from dance floors, this works to emphasize the intimacy from such nights, with a small amount of mystery remaining tethered to the space, rather than being shared on social media.

Ultimately, we have multiple selves and identities, and the responsible worker role, along with its attendant pressures, invites an abandoning on the weekend for a self-expressive pleasure seeker. Out goes the routine of rising early, living healthily and in comes the avoidance of sleeping for long periods of time. There is a yin and yang dualism at play.

The months of physical distancing remaining between now and whenever a vaccine is hopefully discovered will only increase the desire to rekindle that feeling of being a part of something bigger than oneself, of having a collective journey in a subcultural space where the intimate hedonism is inexplicable to those not present and all too understandable for those that are.

No comments:

Post a Comment